FUN FACTS & GRAPHICS:

FLASHBACK: FROM 3 FEDERAL RESERVE INCREASES THAT WERE ORIGINALLY SCHEDULED FOR 2019 TO 3 DECREASES (50 to 75 basis points cut by Fall 2019)?

The Fed is likely to drop ‘patient’ word next week, clearing way for July cut, economists say

KEY POINTS

- When Federal Reserve officials meet next week, they are expected to clear the way for a July interest rate cut by downgrading their economic forecast, tweaking the language in their statement and reducing their interest rate forecasts.

- The Fed is expected to remove the word “patient” from its statement, signaling that it is ready to move on interest rate cuts to help the U.S. economy make it through a period of slower growth and the potential impacts of trade wars.

- Fed funds futures are pointing to odds of about 80% for a July cut and about 20% for a June cut.

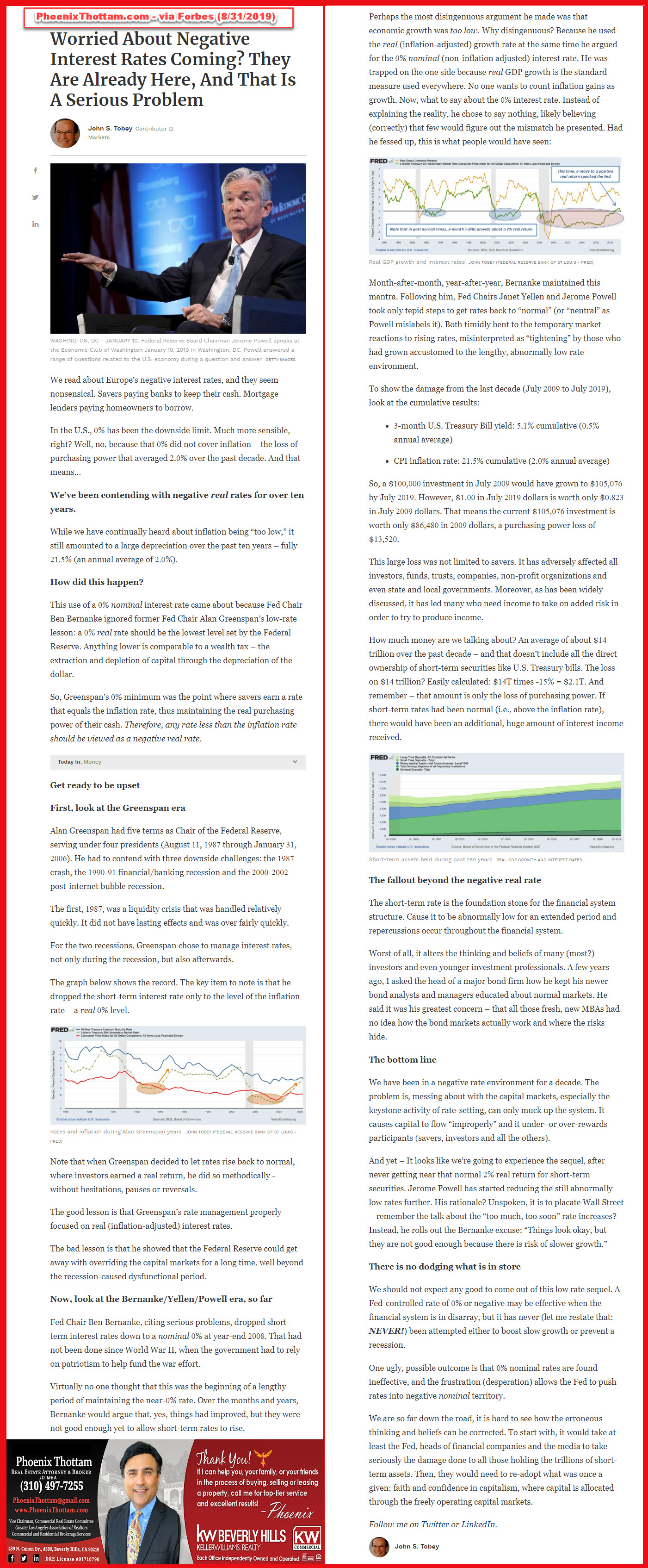

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell holds a press conference following a two day Federal Open Market Committee policy meeting in Washington, U.S., January 30, 2019.

Leah Millis | Reuters

Even with President Donald Trump and the markets calling for lower interest rates, the Fed is not likely to make a move when it meets next week, though it is expected to smooth the way for a rate cut later in the summer.

The timing of a Fed rate cut, the first in more than a decade, is up for debate. But such a move has become more of a given in markets, after May’s weak jobs data and softer-than-expected consumer price inflation.

A growing number of economists and investors are expecting a midsummer rate cut, at the July 30-31 meeting. There are also those who expect the Fed to wait until September, considering more data before cutting rates. Then there are a few, such as economists at Goldman Sachs, who expect no cut at all this year.

Short-Term Rates

The Federal Reserve controls short-term interest rates. The Fed is is currently in the midst of a now stopped hiking cycle that began at 0.25% in December 2008. The S&P 500 actually bottomed three months later, in March 2009, shortly after President Obama first took office. Short-term rates have slowly risen since then, by another 50 bps to 0.75% in late 2016, by an additional 75 bps to 1.50% in 2017, and by another 75 bps to 2.25% thus far in 2018.

Long-Term Rates

The market controls long-term interest rates. The 10-Year Treasury Note is the most widely tracked government debt instrument in finance, and its yield is often used as a benchmark for other interest rates including corporate bonds, agency bonds (Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac), and mortgage rates. Chart 1 below, a monthly chart, shows that the 10-year bottomed near 1.50% twice – at 1.51% in July 2012 and at 1.46% in July 2016, and is currently at 3.07%. The only other time U.S. 10-year yields were as low as 1.50% over the past 100 years was in November 1945, at the end of World War II.

America’s Unemployment Rate Falls to Its Lowest Level in Almost 50 Years

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its monthly Employment Situation Report today, which shows continued evidence of a strong labor market. The U.S. unemployment rate is now the lowest it has been in nearly 50 years, payroll employment continued its historic streak of positive jobs gains, and average weekly wages continued to rise.

BLS’s September survey of households offers evidence of a booming United States economy. The unemployment rate dropped 0.2 percentage points (p.p.) over the month to 3.7 percent, the lowest it has been since December 1969 (see figure below). This is only the tenth month since 1970 that the unemployment rate has been recorded below 4 percent, with five of these months occurring in 2018. We know this decrease in the unemployment rate is due to more people finding jobs, as the labor force participation rate remained unchanged in September.

In addition to the nearly 50-year low for the overall unemployment rate, unemployment also reached historic lows for multiple demographic groups. The unemployment rate for Hispanics fell to 4.5 percent (matching July 2018), the lowest rate ever recorded. For women, the unemployment rate fell to 3.6 percent (matching May 2018), which was the lowest rate in nearly 65 years. The unemployment rate for those with a high school degree and no college attendance hit 3.7 percent, the lowest since April 2001. Furthermore, September was the first month since December 2000 that the number of people who are unemployed fell below 6 million.

The BLS survey of employers, also released today, showed that nonfarm payroll employment rose by 134,000 jobs in September. While below expectations for the month of September, employment gains in August were upwardly revised by 69,000 jobs, now showing 270,000 jobs gained that month—a very healthy number. Including the upward revisions in both July and August, average job growth per month is 208,000 for 2018, exceeding the average monthly gains in 2016 (195,000) and 2017 (182,000). Since President Trump was elected in November 2016, the strong United States economy has created 4.2 million jobs.

Job growth has been strong across the board during the first 20 months of this Administration. Since the President took office, goods-producing industries (construction, manufacturing, and mining and logging) have added almost 900,000 jobs. Of the 14 sectors measured, only retail trade, leisure and hospitality, and other services experienced job losses in September, and the employment decline in leisure and hospitality employment (-17,000) can likely be partially attributed to the effects of Hurricane Florence.

Nominal average hourly earnings rose by 2.8 percent over the past 12 months, while nominal weekly earnings growth was even stronger at 3.4 percent over the past 12 months. This is the fifth consecutive month with nominal 12-month growth over 3 percent—the longest streak with 3 percent nominal weekly earnings growth since 2010. Real wages (which take inflation into account) are also growing. Based on the most recent Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index data from August, inflation in the past year was 2.2 percent (September data will be available later this month).

Current Federal Reserve Interest Rates and Why They Change

Why the Fed Funds Rate Rose to 2.25 Percent

BY KIMBERLY AMADEO September 26, 2018

The current federal funds rate rose to 2.25 percent when the Federal Open Market Committee met on September 26, 2018. This benchmark rate is an indicator of the economy’s health.

The Federal Reserve signaled it would raise rates to 2.5 percent in December 2018, 3.0 percent in 2019, and 3.5 percent in 2020. The rate is critical in determining the U.S. economic outlook.

The 2008 recession caused the Fed to lower its benchmark rate to 0.25 percent. That’s effectively zero. It stayed there seven years until December 2015, when the Fed raised interest rates to 0.5 percent. The fed funds rate controls short-term interest rates. These include banks’ prime rate, most adjustable-rate and interest-only loans, and credit card rates.

-

-

01

FOMC Raised the Rate to 2.5 Percent

The FOMC raised the fed funds rate a quarter point to 2.25 percent on September 26, 2018.

Prior to that, the Fed had raised rates to the following levels:

- 0.5 percent on Dec. 15, 2015.

- 0.75 percent on Dec. 14, 2016.

- 1.0 percent on March 5, 2017.

- 1.25 percent on June 14, 2017.

- 1.5 percent on Dec. 13, 2017.

- 1.75 percent on March 21, 2018.

- 2.0 percent on June 13, 2018.

The Fed finished tapering off its quantitative easing program in 2013. That was a massive expansion of the Fed’s open market operations tool. The Fed still had $4 trillion of debt in 2017 on its books from QE. In October 2017, it began allowing its holdings to gradually decline.

-

-

-

02

Five Steps That Protect You From Rising Interest Rates

The Fed’s higher rates affect your savings, your purchases and your loans. Learn about five things you can do right now to protect your finances.

-

-

-

03

How the Fed Changes the Fed Funds Rate

The FOMC sets a target for the fed funds rate at its regular meeting. Banks charge each other this rate when they lend each other funds. Those are loans banks make to each other to meet the Fed’s reserve requirement. Technically, the banks set these rates, not the Federal Reserve. But banks usually follow whatever rate the Fed sets as its target.

-

-

-

04

How the Fed Funds Rate Works

The FOMC targets a specific level for the fed funds rate. This rate directly influences other short-term interest rates such as deposits, bank loans, credit card interest rates, and adjustable-rate mortgages. By lowering the fed funds rate so dramatically during the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed kept funds available for banks. It signaled to financial markets that the Fed would act decisively to keep banks functioning.

-

-

-

05

How Other Interest Rates Are Determined

The fed funds rate is the most significant leading economic indicator in the world. Its importance is psychological as well as financial. In fact, the only two rates it directly impacts are the prime lending rate and adjustable rate mortgages. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note determines conventional mortgage rates. Find out how the two work in controlling recession and inflation.

-

-

-

06

Historical Fed Funds Rate in 2007 and 2008

The Fed lowered the rate by a half point, to 0.25 percent, on December 16, 2008. That was the 10th rate cut in a little over a year. Previous cuts included:

- Sep. 18, 2007: A 1/2 point cut to 4.75 percent.

- Oct. 31, 2007: A 1/4 point cut to 4.5 percent.

- Dec. 11, 2007: A 1/4 point cut to 4.25 percent.

- Jan. 22, 2008: A 3/4 point cut to 3.5 percent.

- Jan. 30, 2008: A 1/2 point cut to 3 percent.

- March 18, 2008: A 3/4 point cut to 2.25 percent.

- April 30, 2008: A 1/4 point cut to 2 percent.

- Oct. 8, 2008: A 1/2 point cut to 1.5 percent.

- Oct. 29, 2008: A 1/2 point cut to 1 percent.

The Fed’s aggressive expansionary monetary policy was needed to address the 2008 financial crisis.

-

-

-

07

How the Fed Intervened Throughout the Financial Crisis

In August 2007, banks became fearful of loaning each other funds, causing the Libor rate to rise. The Fed initially tried to calm this panic by adding funds to the discount window, hoping that this would restore liquidity and confidence in financial markets. When that didn’t work, the Fed realized it needed to lower the fed funds rate. By 2008, the Fed bailed out Bear Stearns, bought AIG, and made nearly unlimited funds available to banks to prevent global financial market collapse.

-

-

-

08

Historical LIBOR Rates

After the Fed bailed out Bear Stearns, it thought the crisis was over. In April 2008, the Libor started to diverge from the fed funds rate. The Fed lowered the fed funds rate, but LIBOR continued to rise. Despite the Fed’s reassurance, banks continued to panic, and were unwilling to lend to each other. They were afraid of receiving subprime mortgages as collateral. By October 2008, the fed funds rate was 1.5 percent, but Libor was 4.3 percent.

-

-

09

Low Interest Rates Create Asset Bubbles Instead of Inflation

Many people worried that the Fed’s stimulus programs would create inflation. But it didn’t, because the Fed wound down most of the programs that steered the world’s largest economy away from collapse. It also outlined a plan to absorb money the Fed has pumped into banks since August 2007. Instead, the Fed’s policies created asset bubbles in commodities not measured in the Consumer Price Index. Those include bonds, gold, stocks, and the dollar